A new article in Foreign Policy by Colum Lynch and Robbie Gramer does a great job of summing up two reasons that the United States is losing influence over international ordering.

The first is long-term American relative decline. Washington has lost its de facto “patronage monopoly.” This has reduced American leverage over other countries. Governments can, for example, go to China if they want to finance development projects or receive economic aid. Beijing has little interest in even inconsistently and hypocritically promoting political liberties, human rights, and anti-corruption measures. Its primary concern is making the world safe for its own domestic authoritarianism.

The second is the Trump administration’s multi-pronged assault on U.S. diplomatic influence. This includes targeting career diplomats whom it perceives as insufficiently committed to Trump and his policies. It also involves the abdication of American influence in multilateral organizations. As my colleague Lise Howard notes in the Washington Post:

Over the last two and a half years, the United States has struggled to rally support within the U.N. to contain the influence of rival powers from Iran to Russia to China, which has effectively mobilized U.N. backing for its Belt and Road Initiative, despite U.S. efforts to counter it. U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has also largely dismissed repeated warnings from allies and others that its own retreat from multilateral diplomacy would create a vacuum that could promote chaos or leave room for the rise of authoritarian powers such as China.

Lynch and Gramer:

John Sullivan, the U.S. deputy secretary of state, and David Hale, the undersecretary of state for political affairs, touched on those issues during a closed-door town hall meeting on Aug. 29 with IO staffers. But they expressed particular concern about China’s strategic goal of deepening its influence in the U.N. and other international organizations.

The coming months will be “key times” for the bureau to promote U.S. national security interests in international institutions with the upcoming U.N. General Assembly, Hale said, according to an account of the meeting relayed to Foreign Policy. “It’s only gotten harder as we face the increasing attempts, campaigns, by China to gain greater and greater influence over these organizations,” he said.

Over the last two and a half years, the United States has struggled to rally support within the U.N. to contain the influence of rival powers from Iran to Russia to China, which has effectively mobilized U.N. backing for its Belt and Road Initiative, despite U.S. efforts to counter it. U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has also largely dismissed repeated warnings from allies and others that its own retreat from multilateral diplomacy would create a vacuum that could promote chaos or leave room for the rise of authoritarian powers such as China.

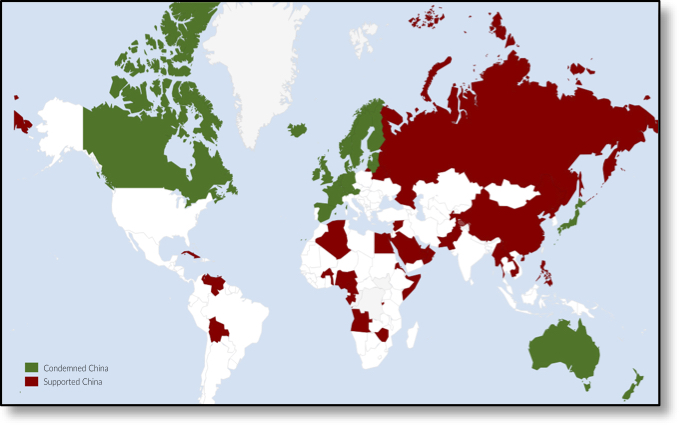

We can see the effects of Chinese increasing economic influence—and the signs of U.S. abdication—very clearly if we look at those countries signing letters supporting or opposing China’s “reeducation” camps in Xinjiang (note that Qatar has since withdrawn its signature).

Alexander Cooley, CC BY-SA 4.0

The United States is exiting, for good or for ill, from global hegemony. That does not mean that the US will cease to play a role in international ordering, either within the “American system” or worldwide. Nor does it require a complete unravelling of the political liberalism baked into global order. But by actively undermining American diplomatic influence in the infrastructure of international order, the Trump administration is certainly making things worse for the United States.