There are a variety of forces pushing the United States toward the exit for global hegemony, but none is quite so frustrating as the Trump administration’s simple abdication from exercising leadership. Trump is doing his best to get the United States out of the game of providing international public and club goods. As Stephen Wertheim pointed out years ago, Trump is giving us the worst of all possible worlds: a reduced American role in multilateral governance conjoined to increased militarism.

In many respects, Trump’s efforts have been stymied by legal and institutional constraints. Trump’s hostility toward proactive and engaged international cooperation still exceeds that of the modal Republican Senator, and it is much easier to undermine many American international commitments than it is to outright destroy them. But when it comes to gutting US diplomatic capacity and leaving the US increasingly diminished in international forums, Trump has met with significant success.

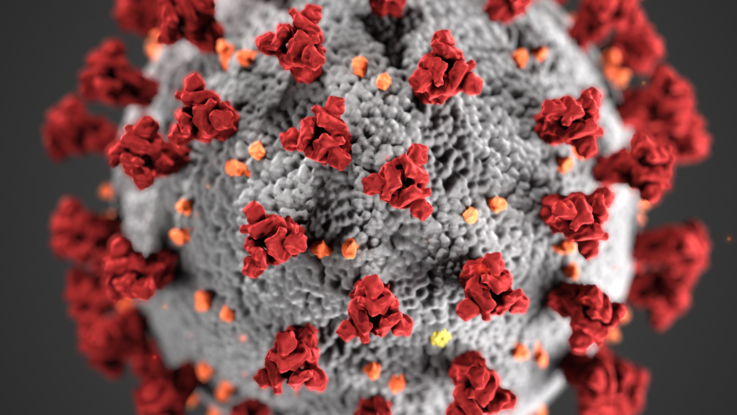

These failures are being thrown into sharp relief by the the COVID-19 crisis. We all know by now that Trump got rid of key institutional capacity to deal with pandemics, especially in terms of national security. It’s also important to stress that while the Federal Reserve remains cognizant of its global economic role, the White House is basically AWOL in terms of taking a proactive part in managing the global dimensions of the pandemic. Trump has consistently failed to effectively coordinate with partners and allies; sometimes he hasn’t even bothered.

This has led a number of commentators to point out the contrast with China.

The status of the United States as a global leader over the past seven decades has been built not just on wealth and power but also, and just as important, on the legitimacy that flows from the United States’ domestic governance, provision of global public goods, and ability and willingness to muster and coordinate a global response to crises. The coronavirus pandemic is testing all three elements of U.S. leadership. So far, Washington is failing the test.

As Washington falters, Beijing is moving quickly and adeptly to take advantage of the opening created by U.S. mistakes, filling the vacuum to position itself as the global leader in pandemic response. It is working to tout its own system, provide material assistance to other countries, and even organize other governments. The sheer chutzpah of China’s move is hard to overstate. After all, it was Beijing’s own missteps—especially its efforts at first to cover up the severity and spread of the outbreak—that helped create the very crisis now afflicting much of the world. Yet Beijing understands that if it is seen as leading, and Washington is seen as unable or unwilling to do so, this perception could fundamentally alter the United States’ position in global politics and the contest for leadership in the twenty-first century.

It’s definitely important to look at recent developments through the lens of contestation over international order. But right now I’m more worried that COVID-19 is a leading indicator of what a post-hegemonic world will look like. China is not likely to achieve anything like the “sole superpower” status the United States enjoyed in the 1990s and early 2000s. As Alex Cooley and I discuss in our book, hopes for effective global governance mostly depend either on some kind of a “G2” arrangements led by the US and the PRC or a great-power cartel of which the US and China are two of the more important players.

In either case, the idea is that we move from “monopolistic” to “oligopolistic” international management. Recent developments do not bode well for this shift. In principle, COVID-19 is ripe for such management. There’s a history of recent coordinated global action on disease, the threat has a high “human security” component, and while there are opportunities for relative gains the fact is that the kind of economic downturn we’re looking at will be bad for everyone. But, instead, oligopolistic management is largely absent. The US and China are focused on blaming one another for the disease – such that tensions are worse than they’ve been in years. If this is prologue, than it looks like the post-hegemonic world will be held together not by common interests in collective problems but by enlightened and effective leadership. And lately, that’s been too scarce a resource for comfort.